I am often asked whether a particular attack was carried out by one botnet or another. The assumed culprit typically changes with whichever botnet is receiving the most media attention at the time. Right now, Aisuru dominates the headlines due to several record-breaking attacks being attributed to it. As a result, any DDoS incident above 1 Tbps inevitably prompts the same question: “Was it Aisuru?”

Attributing DDoS attacks is extremely difficult. There is no reliable fingerprint to identify a specific botnet. Most DDoS-for-Hire platforms offer a wide range of L3/4 and L7 attack options, and the final attack vector mix depends entirely on the ‘customer’ launching the attack. Even when an attacker uses every available option, distinguishing one botnet from another based solely on observed vectors remains challenging.

Attribution based on source IPs is fundamentally unreliable. Direct-path attacks typically rely on random or spoofed sources, while reflection and amplification attacks leverage open relays. Even with many servers available for reflection and amplification, different attackers can easily end up using the same infrastructure, creating significant overlap that further undermines attribution.

On rare occasions, I’ve seen DDoS-as-a-Service platforms deliberately “taint” their payloads for promotional purposes. They insert their name or sometimes offensive language into the packet payload at L3/L4 or into the URL or POST body for L7 attacks. When researchers later report on these incidents, the operators gain attention and effectively receive free advertising.

On rare occasions, I’ve seen DDoS-as-a-Service platforms deliberately taint their payloads for promotional reasons. They insert their name or sometimes offensive terms into the packet payload at L3/L4 or into the URL or POST body for L7 attacks. When researchers later publish analyses of these incidents, the operators gain visibility and essentially receive free advertising.

Inference Based on Attack Characteristics

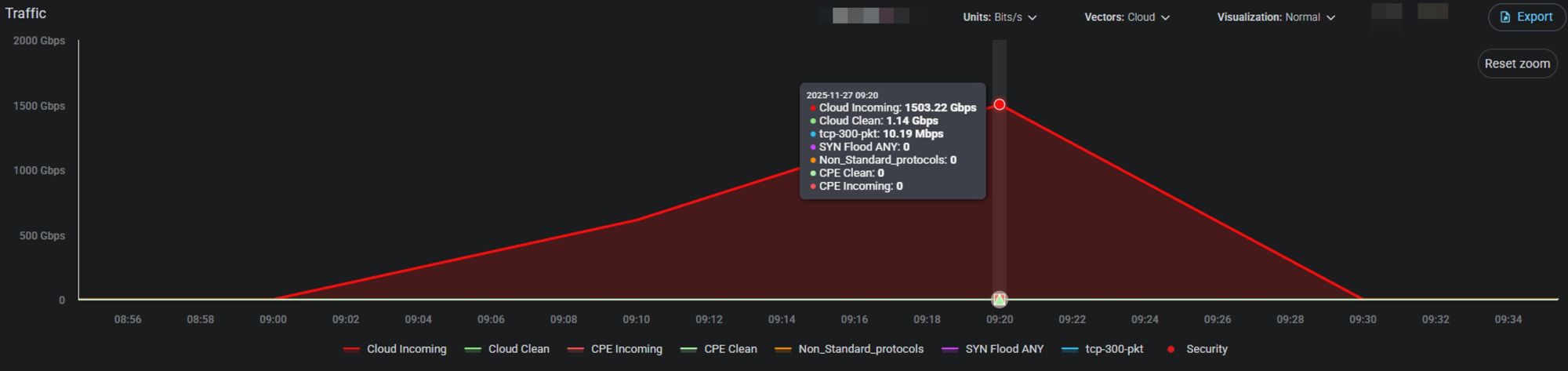

Figure 1 shows a recent attack for which the question arose: “Could this be attributed to Aisuru?”

Figure 1: Attack characteristics of a 1.5Gbps DDoS attack (source: Radware)

Most of the packets in the attack depicted in Figure 1 were blocked by UDP-based ACLs on the cloud ingress infrastructure. A TCP 300-byte packet vector accounted for 10 Mbps, while cloud-clean traffic reached 1.14 Gbps, out of a total of 1.5 Tbps of malicious traffic. Based on the attack data, we can't draw many conclusions. What we can say is that the attack lacked the sophistication to require behavioral algorithms to deter the attack traffic. A few ACLs were sufficient to mitigate most of the 1.5 Tbps malicious traffic. Unsurprisingly, the PCAP samples of the attack also did not provide clues about their ‘creator.’

Was this Aisuru?

It’s possible. But it could just as easily have been any other botnet. Many botnets today exceed 1 Tbps in attack traffic. The recently publicized Shadow and Shadow V2 botnets, for example, generate traffic using compromised Amazon EC2 instances. These make for highly capable bots, and as cloud infrastructure becomes more accessible and bandwidth increases, we can expect average attack volumes to rise accordingly. When AWS experienced an outage in October, Shadow operators were affected as well. In response, they created Shadow V2, which expanded its footprint by scanning for vulnerable IoT devices. Cloud first, IoT as the fallback—criminal operators continue to refine and diversify their playbooks year after year.

The record-setting Aisuru attacks, those exceeding 10 Tbps that were widely covered in the media, generally lasted no more than one or two minutes. The attack depicted in Figure 1 ran for 30 minutes. That alone doesn’t rule out Aisuru. Aisuru operates as a DDoS-for-Hire service with a restricted clientele. The massive, headline-grabbing attacks were likely carried out by the botnet’s operators, who unleashed its full capacity on their targets in search of free advertising. In contrast, a customer commissioning an attack may not request or pay for the entire botnet. It’s common for subscribers or commissioners of DDoS-for-Hire services to receive access only to a portion of the available bots. 60-second attacks typically do not significantly harm the target's reputation, so commissioned attacks tend to last longer, from 30 minutes to several days or weeks.

Conclusion

So, was it Aisuru? Unfortunately, my answer must be: ‘I can’t say for sure. I'm sorry to have to leave you with more questions than answers, but that is the nature of DDoS attack attribution…’

Learn More in our Annual Threat Report